PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

44

INTRODUCTION

I

n the last 25 years the number and variety of enteral

formulas that are available for use has increased dra-

matically. Well over 100 enteral formulas are now

available, making formula selection rather challenging.

In addition, enteral formulas are considered food sup

-

plements by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

and are therefore not under the same regulatory control

as medications. As a result, enteral formula labels may

make “structure and function” claims without prior

FDA review or approval. Furthermore, there is a lack

of prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trials

supporting the purported indications for the majority of

the specialized formulas currently on the market.

Enteral formulas may be classified as standard,

elemental or specialized. Many formulas are available

within each category

, often containing significant dif-

ferences in nutrient composition. Standard enteral for-

mulas are defined as ones with intact protein contain

-

ing balanced amounts of macronutrients and will often

meet a patient’s nutrient requirements at significantly

less cost than specialized formulas (See T

able 1 for

Enteral Formula Selection:

A Review of Selected

Product Categories

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

Carol Rees Parrish, R.D., MS, Series Editor

Ainsley M. Malone, MS, RD, LD, CNSD, Mt. Carmel

West Hospital, Department of Pharmacy, Columbus,

OH.

The availability of specialized enteral formulas has burgeoned in the last 20 years,

many touting pharmacologic effects in addition to standard nutrient delivery. Enteral

formulas have been developed for many specific conditions including: renal failure,

gastr

ointestinal (GI) disease, hyperglycemia/diabetes, liver failure, acute and chronic

pulmonary disease and immunocompromised states. Elemental and fiber supple-

mented formulas are also frequently recommended for use in those with certain types

of gastrointestinal dysfunction. This article will review the rationale for use of special-

ized formulas, provide the supportive evidence, if available, and provide suggestions for

clinical application.

Ainsley Malone

(continued on page 46)

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

46

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

commonly used products). Specialized formulas are

designed for a variety of clinical conditions or disease

states. There are over thirty-five specialized formulas

currently on the market. The purpose of this article is

to review the rationale behind specialized formulas,

provide supportive evidence, if available, and to fur-

nish suggestions for clinical application. Enteral for-

mulas for common food allergies as well as homemade

blenderized formulas are also discussed. Elemental

and immune-modulated formulas will be reviewed in

future issues of

Practical Gastr

oenterology.

STANDARD FORMULAS

Standard formulas comprise the enteral product cate-

gory most often used in patients requiring tube feed-

ings. Their nutrient composition is meant to match that

recommended for healthy individuals. Table 2 pro-

vides a comparison of nutrient sources in polymeric

and hydrolyzed products.

Calorie Dense Products

Nutrient concentrations of standard formulas vary

from 1.0–2.0 kcal/mL and products may or may not

contain fiber. These formulas may be used with vol-

ume sensitive patients or patients needing fluid restric-

tion. Such conditions may include congestive heart

failure, renal failure or syndrome of inappropriate

diuretic hormone (SIADH). However, this intervention

may not always be clinically significant (Table 3). For

example, if a patient requires 1800 kcal/day, changing

a 1.0 calorie/mL to a 2.0-calorie/mL product would

reduce the water content by 900 mL, but to change a

patient from a 1.5 to a 2.0 kcal/mL product represents

a mere 300 mL difference per 24 hour period. Calori

-

cally dense formulas are most practical for use in

patients requiring nocturnal and/or bolus feeding.

FIBER SUPPLEMENTED FORMULAS

Proposed Rationale for Use

Dietary fiber is defined as a structural and storage

polysaccharide found in plants that are not digested in

the human gut (1). Sources of fiber in enteral formulas

include soluble and insoluble (1). A recent fiber addi-

tion to selected formulas (Ross products) is fruc

-

tooligosaccharides (FOS). FOS are defined as short-

chain oligosaccharides and, similar to other dietary

fibers, are rapidly fermented by the colonic bacteria to

short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). SCFA influence gas-

trointestinal function through several mechanisms.

They provide an energy source for colonocytes,

increase intestinal mucosal growth and promote water

and sodium absorption (2). Table 4 provides a listing

of enteral formulas and their fiber content.

Fiber can be classified by its solubility in water.

Soluble fibers, such as pectin and guar

, are fermented

by colonic bacteria providing fuel for the colonocyte,

as described above (1). In addition, increased colonic

sodium and water absorption have been demonstrated

with soluble fiber, a potential benefit in the treatment

of diarrhea associated with EN (2). Insoluble fiber,

such as soy polysaccharide, increases fecal weight,

thereby increasing peristalsis and decreasing fecal

transit time (1).

(continued from page 44)

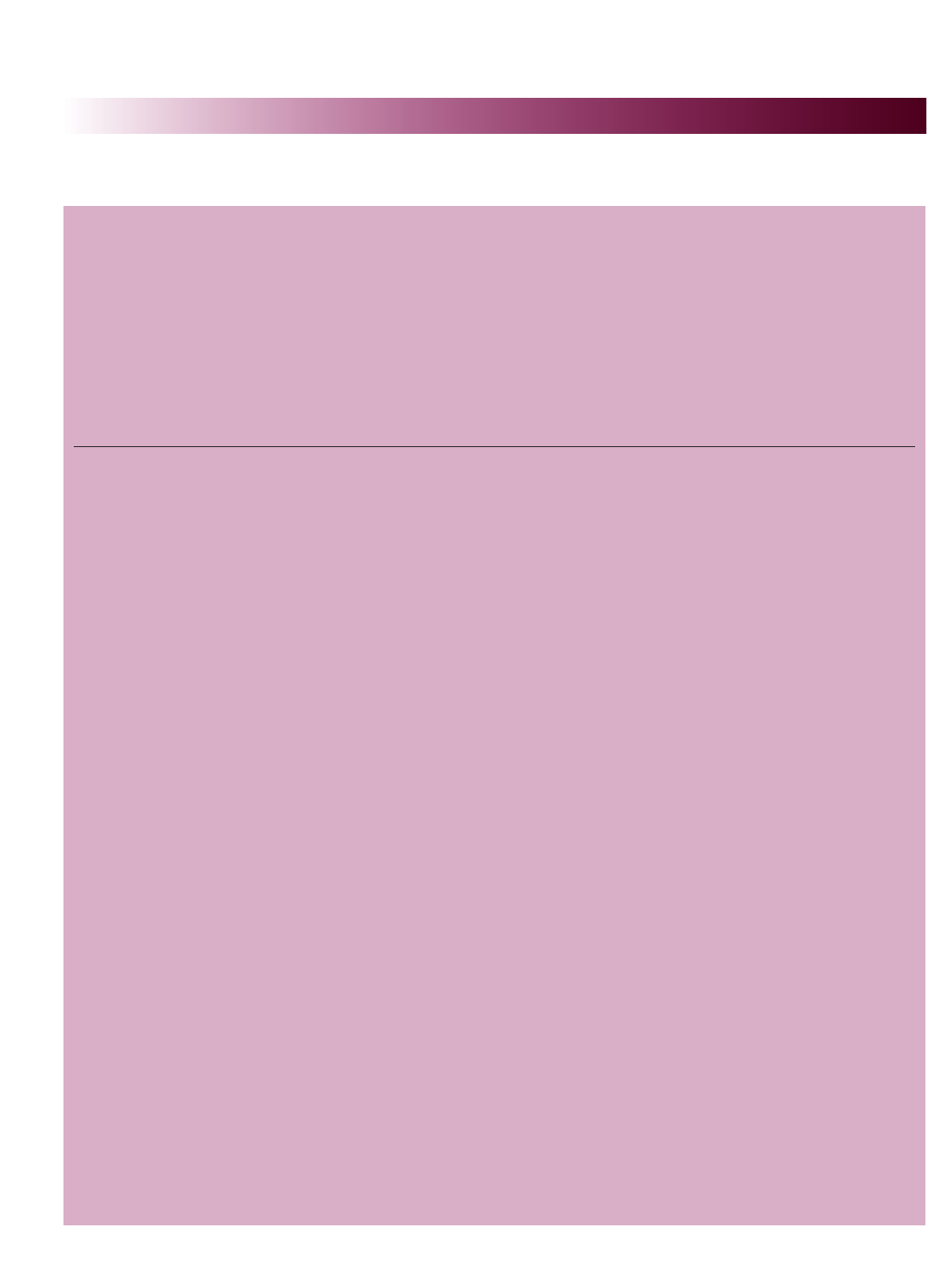

Table 1

C

ost Comparison of Commonly Used Standard Formulas

Cost/

Enteral Formula 1000 Kcals ($)* Company

1.0 cal/mL

Isocal 7.20 Novartis

Nutren 1.0 5.22 Nestle

Osmolite 1.0 5.73 Ross

1.2 cal/mL

Fibersource 1.2 6.13 Novartis

Jevity 1.2 6.50 Ross

Osmolite 1.2 6.08 Ross

Probalance 6.83 Nestle

1.5 cal/mL

Isosource 1.5 4.40 Novartis

Jevity 1.5 6.37 Ross

Nutren 1.5 3.72 Nestle

2.0 cal/mL

Deliver 2.0 4.30 Novartis

Novasource 2.0 3.81 Novartis

Nutren 2.0 2.98 Nestle

TwoCal HN 3.21 Ross

*Based on 1-800 Company Home Delivery Numbers (see Table 17)

(continued on page 48)

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

48

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

Historically

, soluble fiber has been dif

ficult to add

to enteral formulas due to its viscous nature. Many

early fiber supplemented enteral formulas, therefore,

contained soy polysaccharide as their primary fiber

source. Subsequent technological advances have

enabled the inclusion of soluble fiber sources to enteral

formulas and many now contain a combination of both

soluble and insoluble fibers.

Supporting Evidence

Research evaluating fiber

-containing enteral formulas

in the management of diarrhea has demonstrated incon-

sistent results (3–4). This may be related more to the

type of fiber provided rather than the overall fiber

intake. In a small crossover study

, Frankenfield and

Beyer compared insoluble fiber with a fiber free for-

mula in nine head injured enterally fed patients and

found no significant difference in diarrhea incidence

(5). Khalil, et al compared a fiber free formula with a

formula providing insoluble fiber on diarrhea incidence

in sur

gery patients (6). No significant differences in

stool frequency or stool consistency were demonstrated

between groups. Conversely, Shankardass, et al com-

pared long-term enterally fed patients receiving a for

-

(continued from page 46)

(continued on page 50)

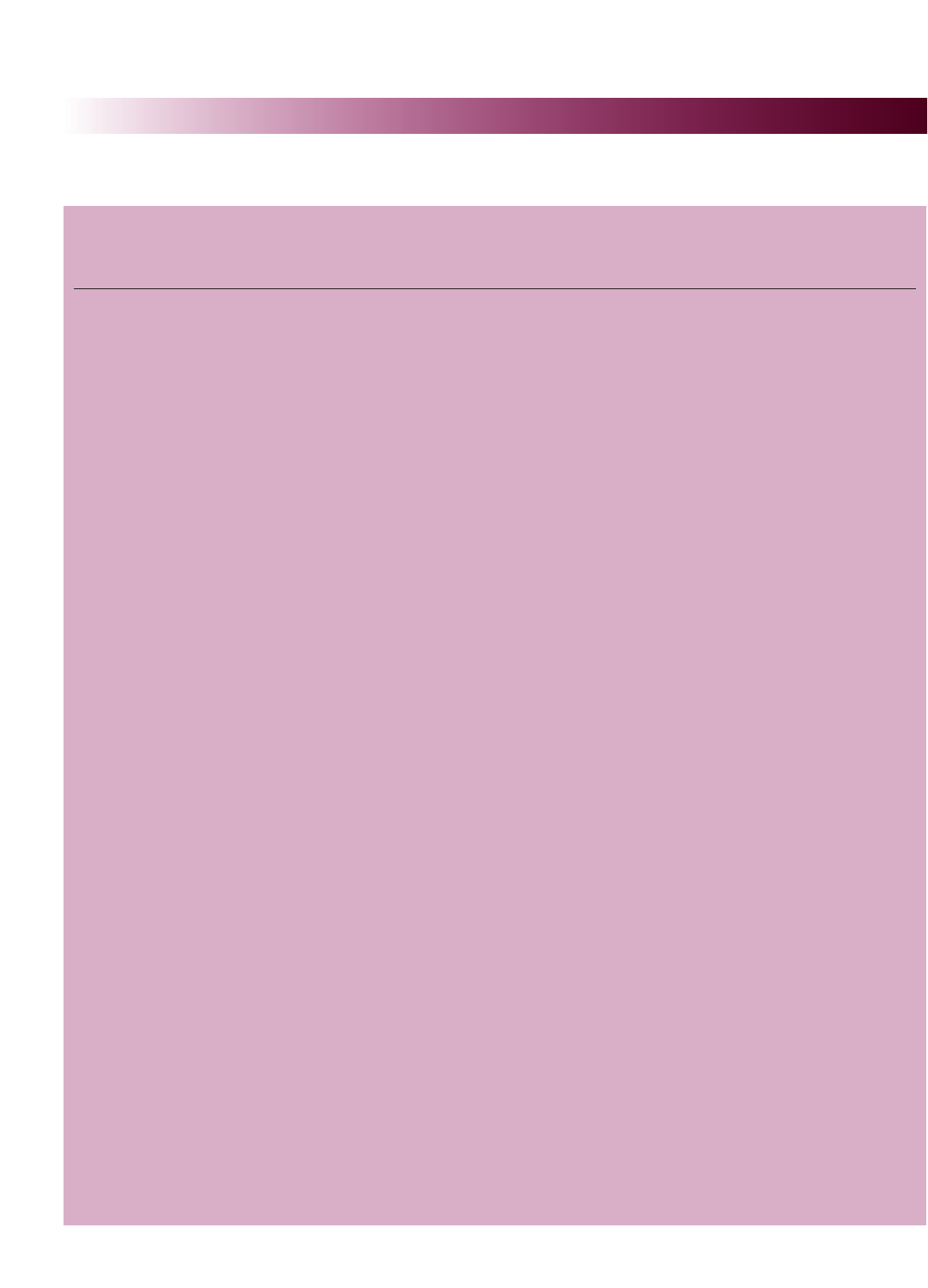

Table 2

M

acronutrient Sources in Enteral Formulas

Enteral Formula Carbohydrate Protein Fat

Polymeric Corn syrup solids Casein Borage oil

Hydrolyzed cornstarch Sodium, calcium, magnesium and Canola oil

Maltodextrin potassium caseinates Corn oil

Sucrose Soy protein isolate Fish oil

Fructose Whey protein concentrate High oleic sunflower oil

Sugar alcohols Lactalbumin Medium chain triglycerides

Milk protein concentrate Menhaden oil

Mono- and diglycerides

Palm kernel oil

Safflower oil

Soybean oil

Soy lecithin

Hydrolyzed Cornstarch Hydrolyzed casein Fatty acid esters

Hydrolyzed cornstarch Hydrolyzed whey protein Fish oil

Maltodextrin Crystalline L-amino acids Medium chain triglycerides

Fructose Hydrolyzed lactalbumin Safflower oil

Soy protein isolate Sardine oil

Soybean oil

Soy lecithin

Structured lipids

Table 3

Water Content of Various Enteral Formula Densities

Caloric Density % Water Volume /1800 kcal (mL) Water by density for 1800 Kcal (mL)

1.0 kcal/mL 84 1800 1530

1.2 kcal/mL 82 1500 1230

1.5 kcal/mL 76 1200 930

2.0 kcal/mL

70 900 630

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

50

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued from page 48)

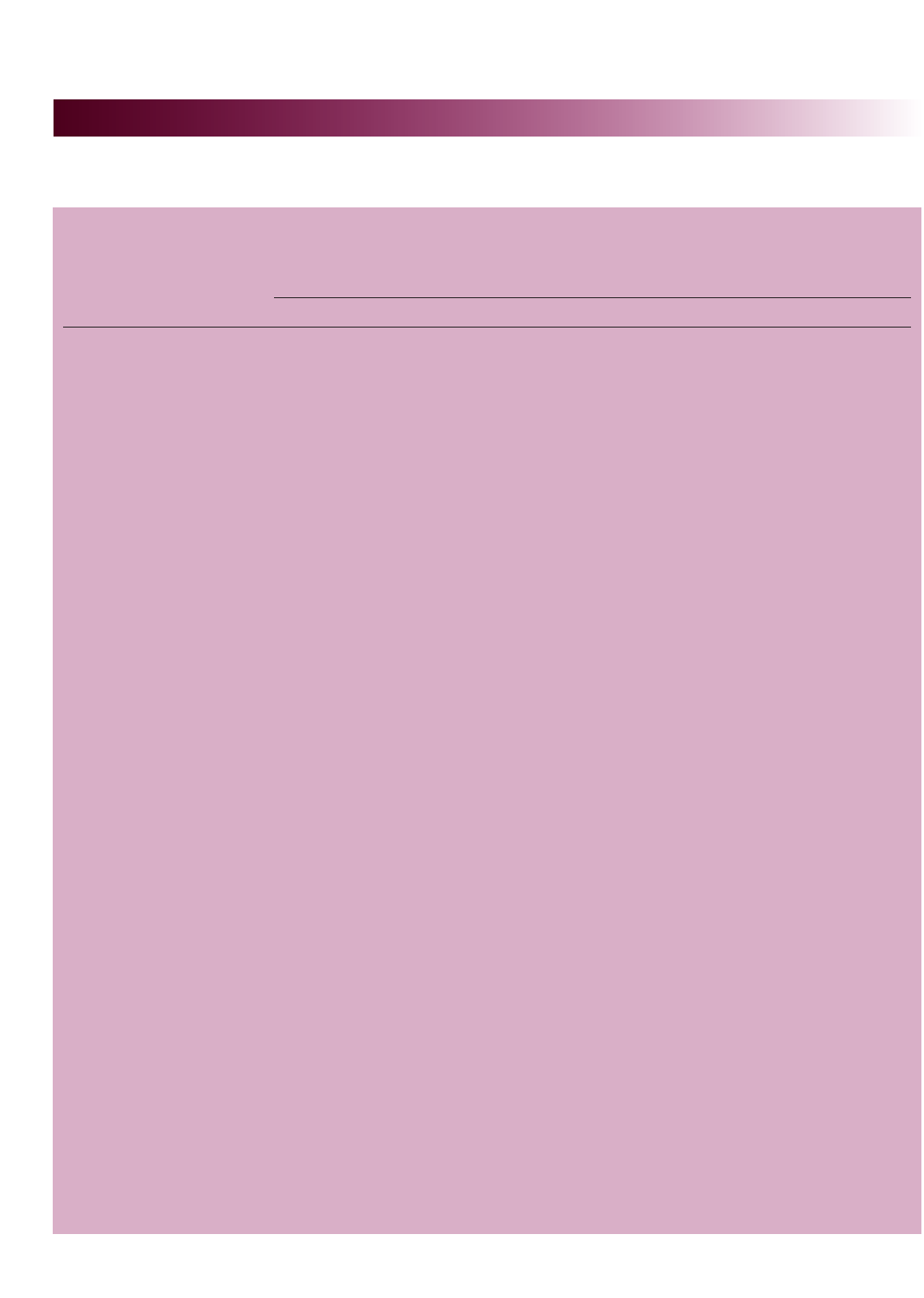

Table 4

F

iber Content of Selected Enteral Formulas

Total Dietary % % Cost /

Product Fiber (g/L) Insoluble Fiber Soluble Fiber 1000 Kcal ($)* Manufacturer

Compleat 4.3 74.0 26.0 10.9** Novartis

Fibersource Std 10.0 75.0 25.0 5.83 Novartis

Fibersource HN 10.0 75.0 25.0 6.13 Novartis

Isosource 1.5 8.0 48.0 52.0 4.40 Novartis

Isosource VHN 10.0 48.0 52.0 8.80 Novartis

Jevity 1.0 14.4 100.0 0.0 6.60 Ross

Jevity 1.2 22.0 75.0 25.0 6.50 Ross

Jevity 1.5 22.0 75.0 25.0 6.37 Ross

Nutren 1.0 w/Fiber 14.0 95.0 5.0 5.98 Nestle

NutriFocus 20.8 75.0 25.0 4.44 Nestle

Novasource Pulmonary 8.0 48.0 52.0 6.72** Novartis

Peptamen w/FOS 4.0 0 100.0 23.76 Nestle

Probalance 10.0 75.0 25.0 6.83 Nestle

Promote w/Fiber 14.4 94.0 6.0 6.60 Ross

Protain XL 9.1 94.0 6.0 5.86** Novartis

Replete w/Fiber 14.0 95.0 5.0 8.45 Nestle

Ultracal 14.4 70.0 30.0 7.70 Novartis

Ultracal Plus HN 10.0 73.0 27 7.23 Novartis

*Based on 1-800 Company Home Delivery Numbers (see Table 17); ** McKesson (800/446-6380)

mula containing insoluble fiber with those on a fiber-

free formula. Fecal weight and number of stools per

day were not significantly dif

ferent between the groups

but the incidence of diarrhea was significantly greater

in the group receiving the fiber-free formula (7). Insol-

uble fiber has not been clearly shown to improve diar-

rhea, especially in the acutely ill patient (3). Soluble

fiber has been associated with more promising results.

In an evaluation of septic, critically ill patients in a

medical intensive care unit (ICU), Spapen, et al com-

pared a soluble fiber with a fiber-free enteral formula.

Frequency of diarrhea was significantly decreased in

those receiving the fiber-supplemented formula (8). In

addition, a recent evaluation of patients in a medical

intensive care unit receiving a soluble-fiber containing

formula (N = 20), demonstrated a decrease in diarrheal

episodes with the fiber-supplemented formula com-

pared to a fiber

-free formula (9).

Use in the Clinical Setting

Enteral formulas supplemented with soluble fiber are

closer to a normal diet; however

, evidence for their use

remains weak. Several cases of bowel obstruction

associated with the use of insoluble fiber-containing

formulas have been reported in the sur

gical and burn

population (10,11). Until further evidence is available,

a fiber-free enteral formula in patients who require

motility suppressing medications and/or are at risk for

bowel obstruction or ischemia may be prudent. In a

recent review of enteral nutrition in the hypotensive

patient, McClave and Chang, 2004, recommend the

use of a fiber-free formula in critically ill patients at

high risk for bowel ischemia (12).

DISEASE SPECIFIC FORMULAS

Renal Disease

Proposed Rationale For Use

Formulas designed for patients with renal disease vary

in protein, electrolyte, vitamin and mineral content

(T

able 5). Generally

, renal formulas are lower in pro

-

(continued on page 52)

(continued from page 50)

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

52

tein, calorically dense and have lower levels of potas-

sium, magnesium and phosphorus when compared to

standard formulas.

Supporting Evidence

There are no clinical trials comparing the efficacy of

renal formulas against standard products.

Use in the Clinical Setting

Formula selection depends upon a patient’s degree of

renal function, the presence or absence of renal

replacement therapy, and the patient’s overall nutrient

requirements. Patients under

going renal replacement

therapy have significantly increased protein require-

ments that may not be met with the current renal for-

mulas available. Persistent hyperkalemia, hyperman

-

ganesemia, hyperphosphatemia is often the driving

factor that leads most clinicians to switch from a stan-

dard formula to a renal product. In patients undergoing

renal replacement therapy, especially continuous veno-

venous hemodialysis (CVVHD), renal formulas are

not always necessary

. These patients typically do not

require fluid restriction and have higher protein

requirements of 1.5–2.0 gm/kg/day (13). In order to

meet the higher protein needs of this patient popula

-

tion, supplemental protein powder is often necessary.

In the absence of elevated levels of potassium, magne-

sium and phosphorus, patients on dialysis should con-

tinue to receive a standard, high-protein formula.

Hepatic Disease

Proposed Rationale for Use

Hepatic formulas of

fer increased amounts of branched

chain amino acids (BCAA): valine, leucine, and

isoleucine; and reduced amounts of aromatic amino

acids (AAA): phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan,

compared to standard products. These alterations have

been purported to promote a reduced uptake of AAA

at the blood brain barrier, reducing the synthesis of

false neurotransmitters and thereby ameliorating the

neurological symptoms that occur with hepatic

encephalopathy (HE) (14). Two enteral formulas with

increased BCAA are available. See Table 6 for formula

characteristics.

Supporting Evidence

Evidence supporting the use of hepatic formulas is

very limited. Several trials evaluating BCAA in

patients with chronic encephalopathy have been con-

ducted in an attempt to determine whether BCAA can

improve neurological outcome or improve tolerance to

dietary protein (15–18). In a multi-center trial, Horst,

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

Table 5

E

nteral Products Designed for Renal Disease

Protein Cost/1000

Product Manufacturer Kcals/mL (gm)** K (mEq)** P (mg)** Mg (mg)** Kcals ($)**

Renal Formulas

Magnacal Renal Novartis 2.0 37.5 16 400 100 3.47

Nepro Ross 2.0 35.0 14 343 108 6.08

NovaSource Renal Novartis 2.0 37.0 14 325 100 5.64

Suplena Ross 2.0 15.0 14 365 108 3.73

Nutri-Renal Nestle 2.0 17.0 Negligible Negligible Negligible 4.17

Standard Concentrated Formulas

Deliver 2.0 Novartis 2.0 37.5 21.5 555 200 4.30

NovaSource 2.0 Novartis 2.0 45.0 19 550 210 3.81

Nutren 2.0 Nestle 2.0 40.0 25 670 268 2.98

Two-Cal HN Ross 2.0 42.0 31 538 213 3.21

*Per 1000 kcals; **Based on 1-800 Company Home Delivery Numbers (see Table 17)

et al (16) compared a BCAA enriched versus a mixed

protein enteral supplement. The BCAA supplemented

group achieved nitrogen balance equal to that of the

control group without precipitation of HE. Additional

studies in which patients were randomized to receive

either an oral diet enriched with BCAA or standard

amino acids failed to demonstrate clinical benefit

(17,18). In a recent publication, Marchesini and col

-

leagues (15) compared the use of an oral BCAA sup

-

plement with either an isonitrogenous standard protein

or isocaloric carbohydrate supplement on mortality,

disease deterioration and the need for hospital admis

-

sion in ambulatory patients with advanced cirrhosis.

BCAA supplementation resulted in a statistically sig

-

nificant (

p = 0.039) decrease in the primary occurrence

events, death, and disease deterioration. The authors

concluded that there are benefits to routinely supple

-

menting BCAA in patients with advanced cirrhosis.

However, the impact of this study is limited by several

factors including a higher drop out rate in the treatment

group. When the results are considered on an “inten

-

tion to treat” basis there is no significant difference in

mortality between the groups. Also, encephalopathy

scores were not significantly different between the

groups. The BCAA enriched group did have greater

improvements in nutritional status, possibly contribut

-

ing to the reduced hospital admissions in that group. In

practice, attention to those factors that limit nutrition

intake, providing an evening snack, and adequate med-

ications to control encephalopathy may be adequate to

allow similar improvements in nutrition status. While

this study suggests a possible benefit to routine BCAA

supplementation, routine use of BCAA in the hospital-

ized patient with HE is not recommended.

Use in the Clinical Setting

The routine use of BCAA enriched enteral formulas in

patients with advanced liver disease and/or HE is not

recommended at this time. Standard enteral formulas

can successfully be used with most patients at a much

lower cost. However

, in those patients who are refrac-

tory to routine drug therapy for HE and are unable to

tolerate standard protein intakes without precipitation

of HE, the use of BCAA enriched enteral formulas

may be worth a short trial.

Diabetes/Hyperglycemia

Proposed Rationale For Use

Several formulas have been developed for use in

patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) (T

able 7). These

formulas offer a lower amount of total carbohydrate

and a higher amount of fat than standard formulas as

well as a variation in type of carbohydrate. Carbohy

-

drate sources generally consist of oligosaccharides,

fructose, cornstarch and fiber. In normal subjects, the

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

53

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued on page 56)

Table 6

E

nteral Formulas Designed for Hepatic Disease

% CHO % Fat % Pro Cost/

Product Manufacturer Kcals/mL Kcals Kcals Kcals Comments 1000 Kcal*

Hepatic-Aid II Hormel Healthlabs 1.2 57.3 27.7 15.0 • Increased levels of leucine, $41.56

isoleucine and valine

• Minimal phenylalanine tryptophan

and tyrosine content

• Contains negligible amounts of

vitamins and minerals

NutriHep Nestle 1.5 77.0 11.0 12.0 • Contains standard amounts $35.55

of vitamins and minerals

• 50% BCAA and 50% AAA

• 66% of fat is MCT

*Based on 1-800 Company Home Delivery Numbers (see Table 17)

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

56

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

use of more complex carbohydrates, such as fructose,

cornstarch and fiber has been shown to improve

glycemic control as a result of delayed gastric empty-

ing and reduced intestinal transit (19). Formulas

designed for patients with DM are based on this

premise. Due to the inherent viscosity of soluble fiber

,

most enteral formulas for DM contain a combination

of soluble and insoluble fiber.

Supporting Evidence

There are few randomized, controlled trials evaluating

diabetic formulas in hospitalized patients with DM. In

a series of two studies, Peters, et al demonstrated that

the use of a diabetic formula results in a reduced

hyperglycemia compared to standard enteral formulas

(20,21). It should be noted that these studies were con

-

ducted in

healthy volunteers using a study protocol

that attempted to mimic continuous tube feeding

administration. Results of these studies cannot be gen-

eralized to hospitalized patients. Craig, et al (22) com-

pared a formula for DM against a standard product in

patients with Type 2 DM residing in a long-term care

facility

. There were no significant differences in

HbgA

1

C or fasting serum glucose levels at baseline,

monthly or at the study completion. Of note, there was

a

trend towards lower infections in the study group.

T

wo recent studies have evaluated diabetic formu

-

las in hospitalized patients. Mesejo, et al compared a

diabetic formula with a standard formula in hyper-

glycemic critically ill patients (23). Mean plasma and

capillary glucose levels as well as units of insulin

infused per day were significantly lower in the diabetic

formula group. There were, however

, no differences in

secondary end points: intensive care unit length of stay,

ventilator days or mortality between the two groups. In

an evaluation of hospitalized type 2 diabetics, Leon-

Sanz, et al compared the effect of a diabetic formula

versus a standard formula on glycemic control (24).

Mean glucose levels, at each of the three weekly mea

-

surement intervals, did not significantly change in those

who received the diabetic formula. Mean glucose levels

in those receiving the standard formula increased signif-

icantly between weeks one and two with no change

occurring in week three. Mean insulin dose was not dif

-

ferent between the two groups during the study period.

The authors concluded the use of a diabetic formula is

associated with a neutral effect on glycemic control. The

clinical significance of the results from this study is

unclear

. The mean blood glucose levels in the diabetic

formula group for all three weeks were >200 mg/dL

ranging from 215–229 mg/dL whereas in the standard

group mean blood glucose levels ranged from 198–229

mg/dL. These results confirm that glucose control is

variable in a hospital setting and that while the use of a

diabetic formula can affect blood glucose levels, the

ef

fect has yet to be shown to be

clinically important.

Furthermore, the important findings of V

an den Ber

ghe

G, et al of a 40% reduction in infectious complications

in a surgical (primarily cardiac) ICU with attention to

tight glucose control via insulin drips, may make these

products even less alluring in the ICU population (25).

Use in the Clinical Setting

Although inviting, the routine use of a formula for DM

is not currently supported by the evidence at this time

(26). However

, in some circumstances when blood

(continued from page 53)

Table 7

E

nteral Formulas Designed for Diabetes Mellitus

% CHO % PRO % FAT Fiber Cost/1000

Product Manufacturer Kcals/mL Kcals Kcals Kcals (g/1000 mL) Kcal ($)*

Choice DM Novartis 1.06 40.0 17.0 43.0 14.4 10.48

DiabetiSource AC Novartis 1.0 36.0 20.0 44.0 4.3 8.33

Glucerna Select Ross 1.0 22.8 20.0 49.0 21.1 **

Glytrol Nestle 1.0 40.0 18.0 420 15.0 8.20

Resource Diabetic Novartis 1.06 36.0 24.0 40.0 12.8 6.22

*Based on 1-800 Company Home Delivery Numbers (see Table 17); **Ross Products was unable to provide this information

glucose control is borderline, and the addition of

insulin may present the greater burden, use of a dia-

betic formula may of

fer an advantage.

Pulmonary Disease

Specialized enteral formulas have been developed for

two types of pulmonary disease: chronic obstructive pul-

monary disease (COPD) and acute respiratory distress

syndrome (ARDS). While there are similarities with

these products, distinct differences do exist (Table 8).

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Rationale for Use

In the 1980’s, reports began to appear describing adverse

ventilatory effects when large amounts of dextrose-based

parenteral nutrition solutions were provided to patients

with and without COPD. The high amounts of dextrose

provided in standard parenteral nutrition formulas were

deemed culpable. This concept was carried over into the

enteral nutrition arena with the introduction of a modi-

fied macronutrient formula designed for the COPD

patient. Substituting a portion of carbohydrate calories

with fat calories was thought to limit carbon dioxide pro-

duction resulting in improved ventilatory status.

Supporting Evidence

Multiple studies comparing the ef

fects of macronutri

-

ent metabolism on respiratory function and status offer

conflicting results. Some have involved ambulatory

COPD patients, while others have evaluated hospital-

ized patients with and without COPD. Therefore, it is

not possible to extrapolate equivocal results to patients

in the hospital setting.

In 1985, Angelillo, et al (27) studied the effect of

fat and carbohydrate content on carbon dioxide (CO

2

)

production in ambulatory COPD patients with hyper-

capnia. They demonstrated both a reduced CO

2

pro

-

duction and respiratory quotient in those who received

a high fat formula. Al-Saady, et al in 1989 (28) com-

pared the ef

fects of a high fat enteral formula with a

standard formula on ventilatory status in hospitalized

patients. Carbon dioxide levels and ventilatory time

were significantly reduced in the high fat formula

group. In a more recent study

, Akrabawi, et al (29) in

1996 evaluated pulmonary function and gas exchange

in ambulatory COPD patients receiving a high fat for-

mula. No significant differences in respiratory quotient

were demonstrated with the high fat formula. Of note,

gastric emptying time was noted to be significantly

longer following the high fat meal, however, the clini-

cal significance of this is unknown.

Early reports citing increased work of breathing

and respiratory failure with lar

ge glucose intake were

found to have provided excessive calories overall (1.7

to 2.25 times the measured ener

gy expenditure). In a

classic study by T

alpers, et al (30), 20 mechanically

ventilated patients received either varying amounts of

carbohydrate (40%, 60% and 75%) or total kcals (1.0,

1.5 and 2.0 times the basal energy expenditure). There

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

57

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

Table 8

F

ormulas Designed for Pulmonary Disease

Product Manufacturer Kcals/mL % CHO Kcals % PRO Kcals % FAT Kcals Cost/1000 Kcals ($)*

COPD Formulas

NovaSource Pulmonary Novartis 1.5 40.0 20.0 40.0 6.72

NutriVent Nestle 1.5 27.0 18.0 55.0 5.33

Pulmocare Ross 1.5 28.2 16.7 55.1 4.28

Respalor Novartis 1.5 40.0 20.0 40.0 7.50

ARDS Formula

Oxepa Ross 1.5 28.1 16.7 55.2 **

*Based on 1-800 Company Home Delivery Numbers (see Table 17); **Ross Products was unable to provide this information

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

58

was no significant difference in vC0

2

among the vary-

ing carbohydrate regimens; however vC0

2

signifi-

cantly increased as the total kcal intake increased. The

authors concluded that avoidance of overfeeding is of

greater significance than carbohydrate intake in avoid-

ing nutritionally related hypercapnia. This lends sup-

port for the argument that reducing total calorie intake

is more important than limiting carbohydrate calories

in preventing adverse ventilatory effects.

Use in Clinical Setting

Overall results demonstrating whether “chronic” pul-

monary enteral products offer a clinical advantage to

the hospitalized patient are inconclusive. In the patient

with chronic pulmonary disease and limited respiratory

reserves, it is critical to monitor PaCO

2

levels in rela-

tionship to overfeeding. The provision of hypocaloric

feeding may be the best option in this type of patient.

Editor’s note: If a patient has an elevated PaCO

2

while

severely hyper

glycemic, then it is unlikely that enteral

nutrition is driving the excess PaCO

2

. Enteral feeding

must not only get into our patients, but also into the

cells to effect CO

2

production.

ARDS

Rationale for Use

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a clin-

ical illness characterized by hypoxemia ultimately

resulting in respiratory failure (31). The cascade of

events that occurs in ARDS is thought to involve alve

-

olar macrophages and their release of pro-inflamma

-

tory eicosanoids derived from the metabolism of

arachidonic acid. Several of these metabolites, throm

-

boxane A2, leukotrienes and prostaglandin E2, have

been implicated in the development of acute lung

injury (32). A specialized enteral formula (T

able 8)

offering a modified lipid component designed to mod-

ulate the inflammatory cascade is available for use

with ARDS. This formula contains borage and fish

oils, sources of g-linolenic and eicosapentanoic acids

as well as increased amounts of antioxidants. The

increased presence of these fatty acids, through meta

-

bolic alterations known to occur in ARDS, lead to an

increased production of prostaglandins of the 1 series

and leukotrienes of the 5 series, metabolites associated

with an anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory state.

Vasoconstriction, platelet aggregation, and neutrophil

accumulation are reduced when the eicosanoid balance

favors anti-inflammatory rather than proinflammatory

mediators (33).

Supporting Evidence

The evidence supporting the use of a specialized

enteral formula for ARDS may have some merit. Pre-

clinical animal data demonstrating positive effects of

eicosapentanoic (EPA) and g-linolenic acids (GLA) on

pro-inflammatory mediator production, gas exchange,

and oxygen delivery work led to the completion of a

multi-center trial (N = 98) evaluating the use of an

ARDS formula in patients with evidence of either

ARDS or acute lung injury (ALI) (33). Patients receiv-

ing the specialized formula showed a significant

improvement in gas exchange, required significantly

fewer days of mechanical ventilatory support, and had

decreased ICU stays compared to the control group.

The authors concluded that the use of a specialized

enteral formula would be useful in the management of

those with or at risk of developing ARDS. However

,

questions have been raised about the possibility that

the high omega-6 fat content of the control formula

may have exacerbated ARDS symptoms.

In a recent report Tehila, et al (34), demonstrated

similar results to the multicenter study by Gadek (33).

Fifty-two ventilated patients with ARDS and/or acute

lung injury were randomized to receive either an

ARDS or control formula. Patients who received the

ARDS formula had a significantly shorter length of

ventilator time as well as a reduced ICU length of stay

compared to the control patients. There was no dif

fer

-

ence in either hospital length of stay or mortality

between the two groups. The study has received criti-

cism in that the control group might have done worse

due to the increased omega-6 fat content of the control

formula vs the beneficial effect of the study formula.

Use in the Clinical Setting

Although promising, the evidence to date does not

support the routine use of a specialized ARDS product

at this time.

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued on page 60)

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

60

ENTERAL FEEDING IN PATIENTS

WITH ALLERGIES

It is important to be aware of the composition of

enteral feeding products for patients with suspected or

documented food allergies. Approximately 20% of the

population in industrialized nations has been reported

to suffer from adverse reactions to food. Nuts, fruits

and milk are the most common triggers (35,36). Epi-

demiological data indicate that these reactions are

caused by different mechanisms, with only about a

third of the reactions in children and 10 percent of

those in adults due to actual food allergy. The majority

of adverse reactions to food are non-immunologic in

origin with lactose intolerance being the most common

type of adverse reaction worldwide. However

, true

food allergies are thought to affect up to 6% to 8% of

children under the age of ten and between 1%–4% of

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued from page 58)

Table 9

R

esources for Food Allergy

• Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network

http://www.foodallergy.org/

• Food Allergy and Intolerances—National Institutes of Health

http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/food.htm

• Food Contents

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Food and Nutrition Information Center

301/436-7725

http://www.nalusda.gov/fnic/index.html

• American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

1/800/842-7777

http://allergy.mcg.edu

Table 10

Formulas/Modulars That Do Not Contain Corn in Product Formulation

This list indicates that the ingredient was not used in the formulation of the product. The production facilities do abide by good manufac-

turing practices, but the products are

NOT represented to be hypoallergenic.* This list does not guarantee complete absence of the ingre-

dient in the product listed under each category. The information contained in this list, although accurate at the time of publication (June

2005), may change due to product reformulation and/or different suppliers providing ingredients for the products. The most current

information may be obtained by referring to product labels.

*Hypoallergenic is defined as “diminished potential for causing an allergic reaction.” Taber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 19th ed. Philadelphia; F.A.

Davis Company, 2001.

Ross Novartis Nestle

Adult Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare (1) None None

Oral Supplements None Arginaid

Boost Breeze

None

Modulars ProMod Benecalorie

Benefiber

Beneprotein

None

Pediatric Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare (1)

Infant Formulas EleCare (1) None None

(1) EleCare is a hypoallergenic, nutritionally complete amino acid-based medical food and infant formula that can be fed to children and adults with

severe, multiple food allergies. EleCare contains corn syrup solids, and is clinically documented to be hypoallergenic, virtually eliminating the potential for

allergic reaction.

Tables 10–15 were prepared by UVAHS dietetic interns: Brandis Thornton and Carolyn Powell, Spring 2005;

Used with permission from the University of Virginia Health System Nutrition Support Traineeship Syllabus

Available at: http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/dietitian/dh/traineeship.cfm.

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

61

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

Table 11

F

ormulas/Modulars That Do Not Contain Casein in Product Formulation

This list indicates that the ingredient was not used in the formulation of the product. The production facilities do abide by good manufac-

turing practices, but the products are NOT represented to be hypoallergenic.* This list does not guarantee complete absence of the ingre-

d

ient in the product listed under each category. The information contained in this list, although accurate at the time of publication (June

2005), may change due to product reformulation and/or different suppliers providing ingredients for the products. The most current

information may be obtained by referring to product labels.

*Hypoallergenic is defined as “diminished potential for causing an allergic reaction.” Taber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 19th ed. Philadelphia; F.A.

Davis Company, 2001.

Ross (1) Novartis Nestle

Adult Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare Diabetisource AC f.a.a.

EquaLYTE Fibersource, Fibersource HN Peptamen, VHP, PreBio 1, 1.5

Isosource, Isosource HN

Subdue Plus

Tolerex

Vivonex Plus, RTF, TEN

Oral Supplements Juven Boost Breeze None

Impact Recover

Peptinex

Resource Arginaid

Resource Arginaid Extra

Modulars Polycose Benefiber None

Beneprotein

Pediatric Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare Vivonex Pediatric Peptamen Junior

Peptamen Junior Powder

Peptamen Junior with PreBio1

Infant Formulas EleCare None Goodstart Essentials

Goodstart Supreme

Goodstart Supreme with DHA & ARA

Goodstart 2 Essentials

Goodstart 2 Supreme with DHA & ARA

Goodstart Supreme Soy with DHA & ARA

Goodstart 2 Essentials Soy

(1) The product manufacturer stipulates these products as having “No Milk in the Product Formulation.” These products are NOT manufactured to be

hypoallergenic, excluding EleCare which is clinically documented to be hypoallergenic.

Tables 10–15 were prepared by UVAHS dietetic interns: Brandis Thornton and Carolyn Powell, Spring 2005;

Used with permission from the University of Virginia Health System Nutrition Support Traineeship Syllabus

Available at: http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/dietitian/dh/traineeship.cfm.

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

62

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued on page 64)

Table 12

F

ormulas/Modulars That Do Not Contain Soy in Product Formulation

This list indicates that the ingredient was not used in the formulation of the product. The production facilities do abide by good manufacturing practices,

but the products are NOT represented to be hypoallergenic.* This list does not guarantee complete absence of the ingredient in the product listed under

each category. The information contained in this list, although accurate at the time of publication (June 2005), may change due to product reformulation

and/or different suppliers providing ingredients for the products. The most current information may be obtained by referring to product labels.

*

Hypoallergenic is defined as “diminished potential for causing an allergic reaction.”

T

aber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary.

1

9th ed. Philadelphia; F.A. Davis Company, 2001.

Ross (1) Novartis Nestle

Adult Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare Compleat (3) Crucial (4)

EquaLYTE Comply (2) f.a.a. (4)

Deliver 2.0 (4) Glytrol (2)

Impact (2), Impact 1.5 (3) Modulen (2)

Isocal HN Plus (2) Nutren 1.0 (2), 1.5 (2), 2.0 (2)

Lipisorb (4) Nutren Fiber (2)

Magnacal Renal (2) NutriHep (2)

Novasource 2.0 (2) NutriRenal (2)

Novasource Renal (2) NutriVent (2)

Peptinex DT (4) Peptamen (4), VHP (4), with PreBio1(4), 1.5 (4)

Respalor (2) Renalcal (2)

Subdue, Subdue Plus Replete (2)

Tolerex

Traumacal (4)

Vivonex Plus (4), TEN, RTF (4)

Oral Supplements Enlive! Boost (2) Carnation Instant Breakfast (2)

Ensure Pudding Boost Plus (2) Carnation Instant Breakfast for the Carb Conscious (2)

Juven Boost Breeze Carnation Instant Breakfast Juice Drink (2)

Impact Recover Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free (2)

Peptinex (4) Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free Plus (2)

Resource Arginaid (2) NutriHeal (2)

Extra 2.0 (2)

Modulars Polycose Benefiber Additions (2)

Beneprotein (2)

Pediatric Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare Compleat Pediatric (4) Nutren Junior (4), Nutren Junior with Fiber (4)

Pediatric Peptinex DT (4) Peptamen Junior (liquid and powder) (4)

Vivonex Pediatric (4)

Peptamen Junior with PreBio1 (4)

Oral Supplements None Resource Just for Kids (4) Carnation Instant Breakfast Junior (2,4)

Infant Formulas

EleCare

None Goodstart Essentials (2,4)

Goodstart Supreme (2,4)

Goodstart Supreme with DHA & ARA (2,4)

Goodstart 2 Essentials (2,4)

Goodstart 2 Supreme with DHA & ARA (2,4)

(1) The product manufacturer stipulates these products as having “No Soy Allergen in the Product Formulation.” These products are NOT manufactured to

be hypoallergenic, excluding EleCare which is clinically documented to be hypoallergenic.

(2) This product contains soy lecithin.

(3) This product contains hydroxylated soy lecithin.

(4) This product contains soy oil or soybean oil.

NOTE: According to the Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network, “studies show that most soy-allergic individuals may safely eat soybean oil (NOT cold

pressed, expeller pressed, or extruded oil) and soy lecithin. Patients should ask their doctors whether or not to avoid these ingredients.” (Reference:

www.foodallergy.org/allergens.html#soy. Highly refined oils (such as soy oil) are not classified as an allergen by Public Law 108-282, August 2, 2004;

however, this law does identify soy lecithin as an allergen. The authors of this table recommend that individuals with soy allergies check with their physi-

cians before using products with soy lecithin or soy oil.

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

64

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued from page 62)

Table 13

F

ormulas/Modulars That Do Not Contain Whey in Product Formulation

This list indicates that the ingredient was not used in the formulation of the product. The production facilities do abide by good manufac-

turing practices, but the products are NOT represented to be hypoallergenic.* This list does not guarantee complete absence of the ingre-

d

ient in the product listed under each category. The information contained in this list, although accurate at the time of publication (June

2005), may change due to product reformulation and/or different suppliers providing ingredients for the products. The most current

information may be obtained by referring to product labels.

*Hypoallergenic is defined as “diminished potential for causing an allergic reaction.” Taber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 19th ed. Philadelphia; F.A.

Davis Company, 2001.

Ross (1) Novartis Nestle

Adult Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare Compleat Crucial

EquaLYTE Comply f.a.a.

Diabetisource AC Glytrol

Fibersource, Fibersource HN Modulen

Deliver 2.0 Nutren 1.0, 1.5, 2.0

Impact, Impact 1.5, Glutamine, with Fiber

Nutren Fiber

Isocal, Isocal HN NutriRenal

Isosource, Isosource HN, 1.5, VHN NutriVent

Magnacal Renal ProBalance

Novasource 2.0, Pulmonary, Renal Replete, Replete with Fiber

Peptinex DT

Protain XL

Respalor

Tolerex

Traumacal

Vivonex Plus, RTF, TEN

Oral Supplements Juven Lipisorb Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free

Resource 2.0, Arginaid Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose

Free Plus

Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose

Free VHC

NutriHeal

Modulars Polycose Benecalorie None

Benefiber

Pediatric Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare Compleat Pediatric None

Pediatric Peptinex DT

Vivonex Pediatric

Infant Formulas EleCare None Goodstart Supreme Soy with DHA & ARA

Goodstart 2 Essentials Soy

(1)The product manufacturer stipulates these products as having “No Milk in the Product Formulation.” These products are NOT manufactured to be

hypoallergenic, excluding EleCare which is clinically documented to be hypoallergenic.

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

65

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued on page 69)

Table 14

F

ormulas/Modulars That Do Not Contain Egg in Product Formulation

This list indicates that the ingredient was not used in the formulation of the product. The production facilities do abide by good manufac-

turing practices, but the products are

NOT represented to be hypoallergenic.* This list does not guarantee complete absence of the ingre-

d

ient in the product listed under each category. The information contained in this list, although accurate at the time of publication (June

2005), may change due to product reformulation and/or different suppliers providing ingredients for the products. The most current

information may be obtained by referring to product labels.

*Hypoallergenic is defined as “diminished potential for causing an allergic reaction.” Taber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 19th ed. Philadelphia; F.A.

Davis Company, 2001.

Ross (1) Novartis Nestle

Adult Products

Tube Feeding Formulas AlitraQ All tube feedings are Crucial

EleCare egg free. f.a.a.

EquaLYTE Glytrol

Glucerna Modulen

Glucerna Select Nutren 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, Fiber

Jevity 1 Cal, 1.2 Cal, 1.5 Cal NutriHep

Nepro NutriRenal

Optimental NutriVent

Osmolite, 1 Cal, 1.2 Cal, 1.5 Cal Peptamen, Peptamen with PreBio1, 1.5, VHP

Oxepa ProBalance

Perative Renalcal

Pivot 1.5 Cal Replete, Replete with Fiber

Promote, Promote with Fiber

Pulmocare

Suplena

TwoCal HN

Vital HN

Oral Supplements Enlive! All liquid oral supplements Carnation Instant Breakfast

Ensure are egg free. Carnation Instant Breakfast for the Carb Conscious

Ensure Fiber with FOS, Healthy Mom Carnation Instant Breakfast Juice Drink

Shake, High Calcium, High Protein, Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free

Plus, Plus HN, Powder, Pudding Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free Plus

Glucerna Shake Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free VHC

Glucerna Weight Loss Shake

NutriHeal

Hi-Cal

Juven

NutriFocus

ProSure Shake

Modulars Polycose None Additions

ProMod

Pediatric Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare All tube feeding formulas Nutren Junior, Nutren Junior with Fiber

PediaSure Enteral Formula are egg free. Peptamen Junior

PediaSure Enteral Formula with Fiber

Peptamen Junior Powder

Peptamen Junior with PreBio1

Oral Supplements PediaSure All oral liquid supplements Carnation Instant Breakfast Junior

PediaSure with Fiber are egg free.

Infant Formulas

EleCare

None

Goodstart Essentials

Goodstart Supreme

Goodstart Supreme with DHA & ARA

Goodstart 2 Essentials

Goodstart 2 Supreme with DHA & ARA

Goodstart Supreme Soy with DHA & ARA

Goodstart 2 Essentials Soy

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

69

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued from page 65)

Table 15

F

ormulas/Modulars That Do Not Contain Gluten in Product Formulation

Ross (1) Novartis Nestle

Adult Products

Tube Feeding Formulas AlitraQ All tube feeding formulas are Crucial

EleCare gluten free EXCEPT Boost f.a.a.

EquaLYTE (3) chocolate malt flavor. Glytrol

Glucerna Modulen

Glucerna Select (3) Nutren 1.0, 1.5, 2.0

Jevity 1 Cal Nutren Fiber

Jevity 1.2, 1.5 Cal (1,2,3) NutriHep

Nepro (3) NutriRenal

Optimental (3) NutriVent

Osmolite, 1, 1.2, 1.5 Cal Peptamen, VHP, with PreBio1, 1.5

Oxepa ProBalance

Perative (3) Renalcal

Pivot 1.5 Cal (3) Replete

Promote Replete with Fiber

Promote with Fiber (2)

Pulmocare

Suplena

TwoCal HN (3)

Vital HN

Oral Supplements Enlive! All liquid oral supplements are Carnation Instant Breakfast Juice Drink

Ensure gluten free EXCEPT Boost Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free

Ensure Fiber with FOS (2,3), chocolate malt flavor. Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free Plus

Healthy Mom Shake, High Calcium, Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose Free VHC

High Protein, Plus, Plus HN, Powder, NutriHeal

Pudding (3)

Glucerna Shake (3), Weight Loss Shake (3)

Hi-Cal

Juven

NutriFocus (1,2,3)

ProSure Shake (3)

Modulars Polycose Benefiber (EXCEPT tablet form) Additions

ProMod

Pediatric Products

Tube Feeding Formulas EleCare All tube feeding formulas Nutren Junior

PediaSure Enteral Formula are gluten free. Nutren Junior with Fiber

PediaSure Enteral Formula with Fiber Peptamen Junior (liquid and powder)

(1,2,3)

Peptamen Junior with PreBio1

Oral Supplements PediaSure All liquid oral supplements None

PediaSure with Fiber are gluten free.

Infant Formulas

EleCare

None

Goodstart Essentials

Goodstart Supreme

Goodstart Supreme with DHA & ARA

Goodstart 2 Essentials

Goodstart 2 Supreme with DHA & ARA

Goodstart Supreme Soy with DHA& ARA

Goodstart 2 Essentials Soy

(1)The patented fiber blend includes oat fiber, soy fiber, carboxymethylcellulose and gum arabic. U.S. Patent 5,085,883.

(2) The oat fiber in Ross products meets the standards for gluten-free ingredients established by the Codex Alimentarius Commission. (Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Pro-

gramme, Codex Alimentarius Commission: Codex Standards for Gluten-Free Foods, in Codex Alimentarius, vol IX, ed 1, 1981; pp. 9-12.)

(3) NutraFlora® brand FOS are produced by the action of the enzyme isolated from Aspergillus niger on sucrose. Ross has exclusive rights for the use of NutraFlora® brand

FOS in adult and pediatric medical nutritional products.

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

70

the adult population, which makes it likely that a sub-

set of patients receiving enteral feeding will have food

allergies. Allergy to cow’s milk, eggs, wheat and soy is

more common in infants and young children while

seafood, peanuts and tree nuts are the more common

causes of food allergy in adult life. In January 2006, a

new law (The Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer

Protection Act of 2004—Public Law 108–282, August

2, 2004) will go into effect requiring food labels to

identify if the product contains any of the 8 major food

aller

gens—crustaceans, egg, fish, milk, peanut, soy

,

tree nuts, and wheat. All food labels must be in com-

pliance by January 1, 2006. See Table 9 for more

resources on food allergies.

Although not an allergy, but an autoimmune

process, patients with celiac disease need to avoid

gluten-containing foods, including enteral formulas

should they be necessary. Tables 10–15 provides a list-

ing of enteral products that may be considered for use

in patients with allergy to corn, casein, soy, whey, egg,

and gluten intolerance.

HOMEMADE/BLENDERIZED ENTERAL FEEDINGS

Most nutrition support clinicians discourage the use of

homemade formulas for several reasons. Blenderized

formulas increase the chance of food borne illness, a

heightened concern in immuno-compromised patients.

In addition, there is an increased work burden on the

patient or caregiver as blenderized formulas can be

very time consuming. Perhaps most important,

blenderized formulas must be carefully made to ensure

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

(continued on page 72)

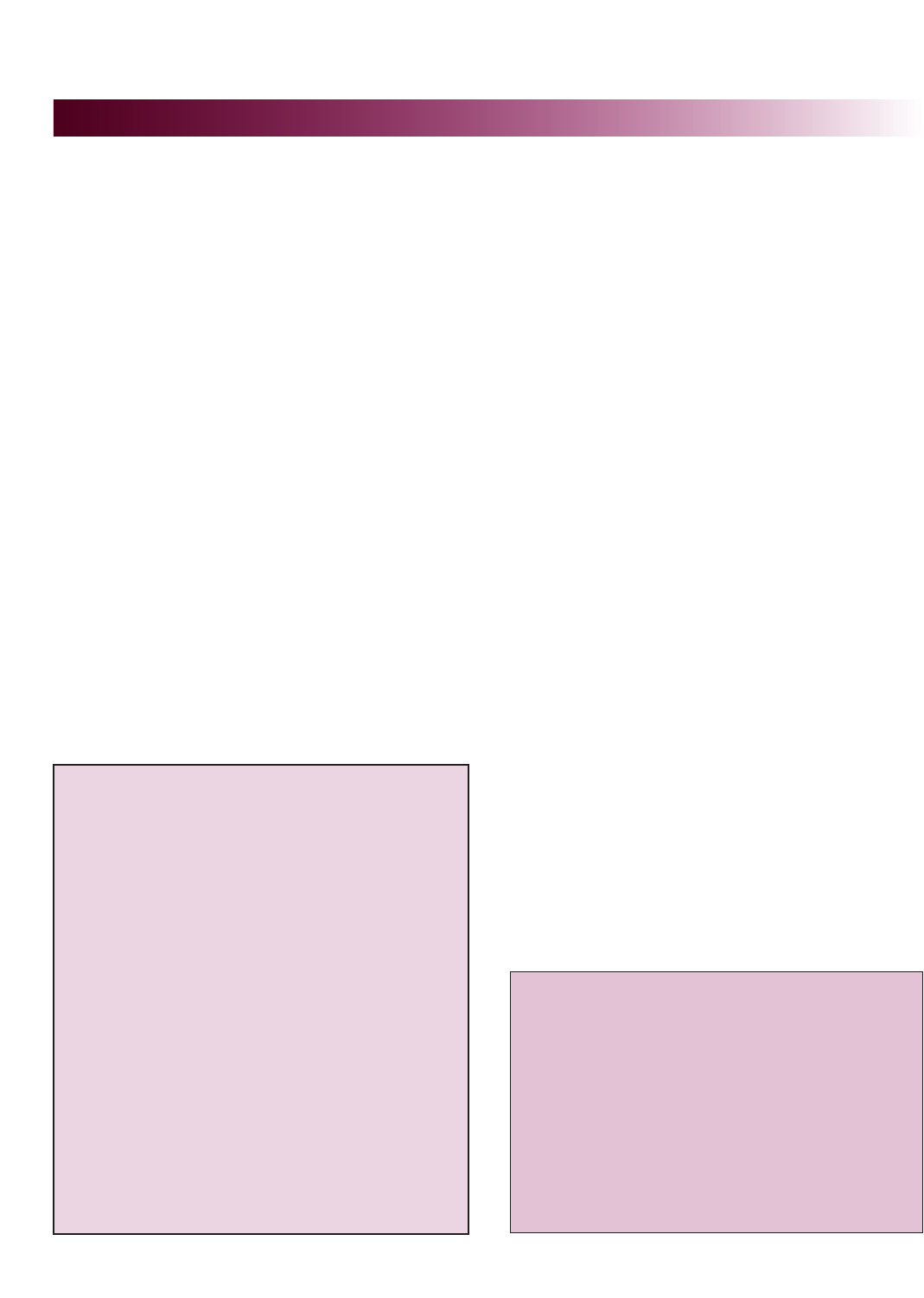

Table 16

B

lenderized Tube Feeding (each recipe is for the whole day)

Calories

6

Ingredients 800 1000 1200 1500 1800 2000 2200 2400 2600 3000

Baby Rice Cereal

(Heinz) (dry)

1

⁄4 cup

1

⁄4 cup

1

⁄4 cup

1

⁄4 cup

1

⁄2 cup

1

⁄2 cup

1

⁄2 cup

1

⁄2 cup

2

⁄3 cup

3

⁄4 cup

Baby Beef

(Heinz) 2.5 oz 2 Jars 2 Jars 2 Jars 2 Jars 2 Jars 2 Jars 3 Jars 3 Jars 3 Jars 3 Jars

Baby Carrots

(Heinz) 4 oz. 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar

Baby Green Beans

(Heinz) 4 oz — — — 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar

Baby Applesauce

(Heinz) 4 oz 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 2 Jars 2 Jars 2 Jars 2 Jars 2 Jars

Baby Chicken

(Heinz) 2.5 oz — — 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 1 Jar 2 Jars

Orange Juice

1

⁄2 Cup

1

⁄2 Cup

1

⁄2 Cup 1 Cup 1 Cup 1 Cup 1 Cup 1

1

⁄2 Cups 1

1

⁄2 Cups 2 Cups

Whole Milk

1

1 Cup 2 Cups 2 Cups 2 Cups 2

1

⁄4 Cups 2

1

⁄4 Cups 3 Cups 3 Cups 3 Cups 3 Cups

Cream, Half-and-Half

1

⁄4 Cup

1

⁄4 Cup

1

⁄3 Cup

3

⁄4 Cup 1

1

⁄4 Cups 1

1

⁄2 Cups 1

1

⁄4 Cups 1

1

⁄2 Cups 1

3

⁄4 Cups 2 Cups

Egg—Cooked

2

11111 2 2 22 2

Vegetable oil

3

1 tsp 2 tsp 1 Tbsp 1 Tbsp 1 Tbsp. 1 Tbsp. 2 Tbsp. 2 Tbsp. 2 Tbsp. 3 Tbsp.

Karo Syrup

4

1 Tbsp 1 Tbsp. 2 Tbsp. 3 Tbsp. 3 Tbsp. 3 Tbsp. 3 Tbsp. 4 Tbsp. 5 Tbsp. 5 Tbsp.

Cost/kcal level

5

$3.09 $3.41 $4.25 $5.11 $5.55 $5.59 $6.85 $7.15 $7.45 $8.56

1

Substitute lactaid milk if needed

2

Pasteurized liquid whole egg can also be used

3

Suggest either: Sunflower, Corn or Soybean Oil (High essential fatty acid content and readily available)

4

Polycose liquid (Ross), can be substituted if necessary; available at www.rosstore.com

5

All items were priced at Super Wal-Mart using Gerber products

6

Makes 1525 mL total volume

Used with permission from the University of Virginia Health System Nutrition Support Traineeship Syllabus

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

72

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

(continued from page 70)

Table 16

B

lenderized Tube Feeding (each recipe is for the whole day) (Continued)

Calorie Levels

3

Nutrients DRIs

1

800 1000 1200 1500 1800 2000 2200 2400 2600 3000

Kcals — 799 989 1205 1478 1784 1986 2216 2408 2600 3002

Protein (g) — 40 48 58 63 71 79 93 96 99 112

Total Fat (g) — 35 47 60 72 89 102 118 126 133 160

Saturated Fat (g) — 16 21 25 32 42 48 51 57 61 68

Monounsaturated (g) — 11 15 19 22 27 31 36 38 40 48

Polyunsaturated (g) — 5 8 12 13 14 15 23 23 24 34

Carbohydrate (g) — 84 95 112 151 181 197 202 234 263 289

Sugar (g) — 35 46 57 79 82 83 91 114 124 137

Fiber (g) —4447799999

Calcium (mg) 1200

673 965 1032 1195 1636 1729 1889 1965 2150 2391

Iron (mg) 10.5 17 17 18 19 33 34 35 35 42 50

Magnesium (mg) 370

154 187 199 250 329 344 374 394 430 488

Sodium (mg) 1500

4

400 520 586 656 744 833 955 1006 1060 1124

Potassium (mg) 4700 1472 1842 1969 2516 2874 3096 3451 3767 3901 4370

Phosphorus (mg) 700 703 930 1019 1152 1491 1643 1815 1887 2029 2252

Zinc (mg) 9.5

6.1 7.0 8.0 8.8 10.1 11 13 14 14 16

Vitamin A (RE) 800 1565 1640 1673 1842 1991 2142 2148 2223 2288 2374

Vitamin C (mg) 82 97 100 101 149 151 195 198 239 240 283

Thiamin (mg) 1.1 1.1 1.2 1.2 1.4 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.9 3.5

Riboflavin (mg) 1.2 1.7 2.1 2.2 2.5 3.4 3.8 4.1 4.2 4.6 5.2

Niacin (mg) 15 14 14 17 17 26 27 29 29 34 41

Pantothenic Acid (mg) 5

2.8 3.5 4.1 4.8 5.3 6.3 7.0 7.4 7.6 8.5

Folate (mcg) 400

92 104 112 176 189 215 227 251 256 290

Vitamin B6 (mg) 1.5 0.7 0.8 1.0 1.1 1.3 1.4 1.6 1.7 1.8 2.1

Vitamin B12 (mcg) 2.4

3.6

4.5

4.9

5.2 5.8 6.6 8.0 8.2 8.4 8.9

Vitamin D (mcg) 10

133 230 234 250 294 330 394 403 413 423

Vitamin E (mg) 15

6.8 10.8 15 16 16 17 29 29 30 42

Vitamin K (mcg)

105

39

49 49 52 54 80 87 91 91 93

Water %

2

— 64 62 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64

1

The average recommended value for a healthy male or female adult. For more information: http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/etext/000105.html

2

Water may need to be added to thin down the formula; furthermore, separate water bolus’ will be needed to meet hydration needs.

3

Numbers shaded and in bold print highlight those nutrients that fall below the average DRI’s for adults – a Centrum vitamin/mineral supplement (or

equivalent) can be crushed and flushed 4-7 days per week as needed to ensure nutrient adequacy of tube feeding.

4

In some circumstances, additional sodium may need to be added to these mixtures.

Used with permission from the University of Virginia Health System Nutrition Support Traineeship Syllabus

nutritional adequacy, a challenging task for the care-

giver. Although there is one commercially prepared

blenderized product on the market (Compleat), it is

significantly more expensive than standard enteral

products.

Nevertheless, some patients or caregivers have a

strong desire to provide “home-made” nutrition.

Table 16 provides recipes adapted from the “olden

days” (circa 1980) for such cases. Ideally, should

patients/families want to use this guide as their sole

source of nutrition, clinicians can suggest varying

foods somewhat within the food categories to increase

variety in the diet. Another way to address the desire

to provide homemade formula is to suggest the family

make an occasional “homemade meal” vs formula for

the entire day on a regular basis.

A few of the lower calorie levels do not provide

100% of the RDI’s; a liquid therapeutic vitamin/min-

eral (or tab crushed and flushed) can be supplemented

to ensure nutrient adequacy. Routine monitoring of a

patient’

s nutritional status with serial weights and lab

values as appropriate, should continue as long as the

patient requires enteral feeding.

CONCLUSION

Enteral formula selection can be challenging and is not

always guided by clinical evidence or clinical practi-

cality. The growth of formula availability has resulted

in a large number of specialized products marketed for

improving specific disease states or conditions. It is

important to critically evaluate these products in con

-

junction with the available supporting clinical evi

-

dence. Until clinical evidence guides us otherwise,

standard formula should be the product of choice for

the majority of patients requiring enteral feeding. For

manufacturer contact information about enteral prod-

ucts discussed in this article, see T

able 17.

n

References

1.

Compher C, Seto RW, Lew JI, Rombeau JL. Dietary fiber and its

clinical applications to enteral nutrition. In: Rombeau JL and

Rolandelli RH (eds),

Clinical Nutrition: Enteral and Tube

Feeding,

3rd edition. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1997,

81-95.

2. Mortensen PB, Clausen MR. Short-chain fatty acids in the human

colon: relation to gastrointestinal health and disease.

Scand J

Gastroenterol,

1996;31 Suppl 216:132-148.

3. Dobb GJ, Towler SC. Diarrhea during enteral feeding in the crit-

ically ill: a comparison of feeds with and without fiber. Intens

Care Med,

1990;16:252-255.

4. Belknap D, Davidson LJ, Smith CR. The effects of psyllium

hydrophilic mucilloid on diarrhea in enterally fed patients.

Heart

Lung,

1997; 26:229-237.

5. Frankenfield DC, Beyer PL. Soy-polysaccharide fiber: effect on

diarrhea in tube-fed, head-injured patients.

Amer J Clin Nutr,

1989;50:533-538.

6. Khalil L, Ho KH, Png D, Ong CL. The effect of enteral fibre-con-

taining feeds on stool parameters in the post-surgical period.

Sin-

gapore Med J,

1998;39:156-159.

7. Shankardass K, Chuchman S, Chelswich K, et al. Bowel function

of long-term tube-fed patients consuming formulas with and

without dietary fiber.

J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 1990;14:508-512.

8. Spapen H, Diltoer M, Malderen CV, et al. Soluble fiber reduces

the incidence of diarrhea in septic patients receiving total enteral

nutrition: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, and con-

trolled trial.

Clin Nutr, 2001;20:301-305.

9. Rushdi TA, Pichard C, Khater YH. Control of diarrhea by fiber-

enriched diet in ICU patients on enteral nutrition: a prospective

randomized controlled trial.

Clin Nutr, 2004; 23:1344-1352.

10. Scaife CL, Saffle JR, Morris SE. Intestinal obstruction secondary

to enteral feedings in burn trauma patients.

J Trauma,

1999;47:859-863.

11. McIvor AC, Meguid MM, Curtas S, Kaplan DS. Intestinal

obstruction from cecal bezoar; a complication of fiber-containing

tube feedings.

Nutrition, 1990;6:115-117.

12. McClave SA, Chang WK. Feeding the hypotensive patient: does

enteral feeding precipitate or protect against ischemic bowel?

Nutr Clin Pract, 2003;18:279-284.

13. Weiner FR. Nutrition in acute renal failure.

J Renal Nutr,

1994;4:97-99.

14. Fischer JE. The role of plasma amino acids in hepatic

encephalopathy.

Surgery, 1975; 78:276-290.

15. Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Merli M, et al. Nutritional supplemen-

tation with branched-chain amino acids in advanced cirrhosis: a

double-blind, randomized trial.

Gastroenterology, 2003;

124:1792-1801.

T

able 17

Enteral Product Manufacturer Contact Information

Nestle Clinical Nutrition

N

estlé InfoLink Product and Nutrition Information Services

1-800-422-2752

Monday–Friday 8:30

A

M

–5 P

M

CST

www.nestleclinicalnutrition.com

Novartis Nutrition

Novartis Medical Nutrition Consumer and Product Support

1-800-333-3785 (choose Option 3)

Monday–Friday 9:00

A

M

– 6:00 P

M

EST

http://www.novartisnutrition.com/us/home

Ross Products Division, Abbott Laboratories

Ross Consumer Relations

1-800-227-5767

Monday–Friday 8:30

AM–5:00 PM EST

www.ross.com

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

73

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

16. Horst D, Grace ND, Conn HO, et al. Comparison of dietary pro-

tein with an oral, branched chain enriched amino acid supplement

i

n chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy: a randomized con-

trolled trial.

Hepatology, 1984;4:279-287.

17. Cerra FB, Cheung NK, Fischer JF. Disease specific amino acid

infusion in hepatic encephalopathy: a prospective, randomized,

double-blinded controlled trial.

J Parenter Enteral Nutr,

1985;9:288-295.

18. Michel H, Bories P, Aubin JP, et al. Treatment of acute hepatic

encephalopathy in cirrhotics with branched-chain amino acid

enriched versus a conventional amino acid mixture.

Liver,

1985;5:282-289.

19. Wolf BW, Wolever TM, Lai CS, et al. Effects of a beverage con-

taining an enzymatically induced-viscosity dietary fiber, with or

without fructose, on the postprandial glycemic response to a high

glycemic index food in humans.

Eur J Clin Nutr, 2003;57:1120-

1127.

20. Peters AL, Davidson MB. Lack of glucose elevation after simu-

lated tube feeding with a low-carbohydrate, high fat enteral for-

mula in patients with type 1 diabetes.

Am J Med, 1989;87:178-181.

21. Peters AL, Davidson MB. Effects of various enteral feeding prod-

ucts on postprandial blood glucose response in patients with type

I diabetes.

J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 1992; 16:69-74.

22. Craig LD, Nicholson S, Silverstone FA, Kennedy RD. Use of a

reduced carbohydrate, modified-fat enteral formula for improv-

ing metabolic control and clinical outcomes in long-term care res-

idents with type 2 diabetes: results of a pilot trial.

Nutrition,

1998;14: 529-534.

23. Mesejo A, Acosta JA, Ortega C, et al. Comparison of a high-pro-

tein disease-specific enteral formula with a high-protein enteral

formula in hyperglycemic critically ill patients.

Clin Nutr,

2003;22:295-305.

24. Leon-Sanz M, Garcia-Luna PP, Planas M, et al. Glycemic and

lipid control in hospitalized type 2 diabetic patients: evaluation of

2 enteral nutrition formulas (low carbohydrate-high monounsatu-

rated fat vs high carbohydrate.

J Parenter Enteral Nutr,

2

005;29:21-29.

25. Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive Insulin

Therapy in Critically Ill Patients.

N Engl J Med, 2001;345:1359-

1367.

26. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors and Clinical Guidelines Task

Force. Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in

adult and pediatric patients.

J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2002; 26.

27. Angelillo VA, Sukhdarshan B, Durfee B, Dahl J, Patterson AJ,

O’Donohue WJ Jr. Effects of low and high carbohydrate feedings

in ambulatory patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-

ease and chronic hypercapnia.

Ann Intern Med, 1985;103:883-

885.

28. Al-Saady NM, Blackmore CM, Bennett ED. High fat, low carbo-

hydrate, enteral feeding lowers PaCO

2

and reduces the period of

ventilation in artificially ventilated patients.

Intensive Care Med,

1989;15:290-195.

29. Akrabawi SS, Mobarhan S, Stoltz R, Ferguson PW. Gastric emp-

tying, pulmonary function, gas exchange, and respiratory quotient

after feeding a moderate versus high fat enteral formula meal in

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients.

Nutrition,

1996;12:260-265.

30. Talpers SS, Romberger DJ, Bunce SB, Pingleton SK. Nutrition-

ally associated increased carbon dioxide production: excess total

calories vs high proportion of carbohydrate calories.

Chest,

1992;102:551-555.

31. Hudson LD, Steinberg KP. Acute respiratory distress syndrome:

clinical features, management and outcome. In: Fishman AP, ed.

Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders. New York:McGraw-Hill;

1998:2549-2565.

32. Karlstad MD, Palombo JD, Murray M, DeMichele SJ. The anti-

inflammatory role of g-linolenic and eicosapentanoic acids in

acute lung injury. In: Haung YS, Mills DE (eds),

Gamma

Linolenic Acid: Metabolism and Its Roles in Nutrition and Medi-

cine,

Champaign, IL: AOCS Press, 1996,137-167.

33. Gadek J, DeMichele S, Karlstad M, Murray M, et al. Effect of

enteral with eicosapentanoic acid, g-linolenic acid, and antioxi-

dants in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Crit

Care Med,

1999; 27:1409-1420.

34.

Tehila M, Gibstein L, Gordgi D, Cohen JD, Shapira M, Singer P.

Enteral fish oil, borage oil and antioxidants in patients with acute

lung injury (ALI).

Clin Nutr, 2003;22(S1):S20.

35. Bischoff S, Crowe SE. Food allergy and the gastrointestinal tract.

Curr Opin Gastroenter, 2004;20:156-161.

36. Crowe SE, Bischoff SC. Gastrointestinal food allergy: New

insights into pathophysiology and clinical perspectives.

Gas-

troenterology,

2005;128(4):1089-1113.

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • JUNE 2005

74

Enteral Formula Selection

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #28

P

P

R

R

A

A

C

C

T

T

I

I

C

C

A

A

L

L

G

G

A

A

S

S

T

T

R

R

O

O

E

E

N

N

T

T

E

E

R

R

O

O

L

L

O

O

G

G

Y

Y

RR EE PP RR II NN TT SS

RR EE PP RR II NN TT SS

Practical Gastroenterology reprints are valuable,

authoritative, and informative. Special rates are

available for quantities of 100 or more.

For further details on rates or to place an order:

Practical Gastroenterology

Shugar Publishing

99B Main Street

Westhampton Beach, NY 11978

Phone: 631-288-4404

Fax: 631-288-4435

There isn’t a physician who hasn’t at least

one “Case to Remember” in his career

.

Share that case with

your fellow gastroenterologists.

Send it to Editor: Practical Gastroenterology,

99B Main Street, Westhampton Beach, NY

11978. Include any appropriate illustrations.

Also, include a photo of yourself.